Introduction

When performing malware analysis, one of the most common techniques of hiding strings is by simply “stacking” them or building them into a buffer to be called later. This technique has been discussed time and time again, but it’s not uncommon to find new pieces of malware that use this.

Understanding string stacking is important because many malware analysis tools still rely (and display) strings alone. In some cases, the tool will show the ascii strings and omit the unicode strings, which is an even worse situation.

When reading through security blog posts, another theme is the high barrier of entry that exists in malware analysis. IDA Pro is expensive and while the tool is very nice, it’s not always available. BinaryNinja attempts to solve this problem but still costs money. Cutter, on the other hand, is free to download and use.

In this blog post we’ll be writing a simple script to rebuild stack strings and automatically add comments to a binary.

This script should give a fairly gentle introduction to writing a plugin that can interface with Cutter and Radare2. Before writing a plugin, let’s understand string stacking techniques more in-depth.

Stacking String, 1, 4, 8 bytes at a time

Consider the following elementary C-code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

char one[14] = "goodbye ";

time_t t;

srand((unsigned) time(&t));

if( (rand() % 10) >= 5 ){

strcat(one, "world");

}

else {

strcat(one, "moon");

}

printf("%s\n", one);

return 0;

}

When running strings against the compiled binary, the following strings appear (using rabin2 -zzz for strings output):

019 0x0000079a 0x0000079a 9 10 (.text) ascii goodbye H

020 0x000007cc 0x000007cc 5 7 (.text) utf8 zgfff

021 0x0000081d 0x0000081d 5 6 (.text) ascii worlf

022 0x00000854 0x00000854 4 5 (.text) ascii moon

These results are expected – the ascii strings show up in the .text (executable code) section of the binary. If the intent is to hide these strings from a simple strings-like utility, the characters of the string can be broken up and placed individually into a char array.

The following code is a similar program, now with strings broken up into individual characters.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

char one[14];

// byte MOVs

one[0] = 'g';

one[1] = 'o';

one[2] = 'o';

one[3] = 'd';

one[4] = 'b';

one[5] = 'y';

one[6] = 'e';

one[7] = ' ';

if (rand() == 0) {

one[8] = 'w';

one[9] = 'o';

one[10] = 'r';

one[11] = 'l';

one[12] = 'd';

one[13] = 0;

printf("%s\n", one);

} else {

one[8] = 'm';

one[9] = 'o';

one[10] = 'o';

one[11] = 'n';

one[12] = 0;

one[13] = 0;

printf("%s\n", one);

}

return 0;

}

When running strings against the compiled output, the strings “goodbye” “world” and “moon” no longer appear.

In a hexdump the following characters are still able to be seen, but because of the opcodes responsible for placing them into the array the strings utility is no longer recognizes the sequence of characters as a contiguous string.

Below is a hexdump of the string being constructued:

000007a0 9c fe ff ff 89 c7 e8 85 fe ff ff c6 45 ea 67 c6 |............E.g.|

000007b0 45 eb 6f c6 45 ec 6f c6 45 ed 64 c6 45 ee 62 c6 |E.o.E.o.E.d.E.b.|

000007c0 45 ef 79 c6 45 f0 65 c6 45 f1 20 e8 80 fe ff ff |E.y.E.e.E. .....|

000007d0 89 c1 ba 67 66 66 66 89 c8 f7 ea c1 fa 02 89 c8 |...gfff.........|

000007e0 c1 f8 1f 29 c2 89 d0 c1 e0 02 01 d0 01 c0 29 c1 |...)..........).|

000007f0 89 ca 83 fa 04 7e 26 c6 45 f2 77 c6 45 f3 6f c6 |.....~&.E.w.E.o.|

00000800 45 f4 72 c6 45 f5 6c c6 45 f6 64 c6 45 f7 00 48 |E.r.E.l.E.d.E..H|

00000810 8d 45 ea 48 89 c7 e8 f5 fd ff ff eb 24 c6 45 f2 |.E.H........$.E.|

00000820 6d c6 45 f3 6f c6 45 f4 6f c6 45 f5 6e c6 45 f6 |m.E.o.E.o.E.n.E.|

00000830 00 c6 45 f7 00 48 8d 45 ea 48 89 c7 e8 cf fd ff |..E..H.E.H......|

When opening this with a disassembler it becomes obvious how these bytes are treated.

| 0x000007a6 e885feffff call sym.imp.srand ; void srand(int seed)

| 0x000007ab c645ea67 mov byte [local_16h], 0x67 ; 'g'

| 0x000007af c645eb6f mov byte [local_15h], 0x6f ; 'o'

| 0x000007b3 c645ec6f mov byte [local_14h], 0x6f ; 'o'

| 0x000007b7 c645ed64 mov byte [local_13h], 0x64 ; 'd'

| 0x000007bb c645ee62 mov byte [local_12h], 0x62 ; 'b'

| 0x000007bf c645ef79 mov byte [local_11h], 0x79 ; 'y'

| 0x000007c3 c645f065 mov byte [local_10h], 0x65 ; 'e'

| 0x000007c7 c645f120 mov byte [local_fh], 0x20 ; "@"

| 0x000007cb e880feffff call sym.imp.rand ; int rand(void)

Similar to how the code is written in the source C, the bytes are stored a single char at a time into offsets into a local array.

This code can be rewritten to do 4 byte mov’s (hex encoded string is “Error Command”).

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

unsigned char* stack_string[20];

((uint32_t*)stack_string)[0] = 0x68656c6c;

((uint32_t*)stack_string)[1] = 0x6f20776f;

((uint32_t*)stack_string)[2] = 0x726c6420;

((uint32_t*)stack_string)[3] = 0x6869;

printf("%s\n", stack_string);

return 0;

}

Which when running strings, we can see parts of the full string.

007 0x0000045c 0x0040045c 5 6 (.text) ascii $Erro

008 0x00000465 0x00400465 4 5 (.text) ascii r Co

009 0x0000046a 0x0040046a 7 8 (.text) ascii D$\bmman

010 0x00000472 0x00400472 7 8 (.text) ascii D$\fd.\r\n

When viewing the output in a disassembler, the DWORDS are stored in a local buffer.

| 0x0040045a c70424457272. mov dword [rsp], 0x6f727245 ; [0x6f727245:4]=-1

| 0x00400461 c74424047220. mov dword [local_4h], 0x6f432072 ; [0x6f432072:4]=-1

| 0x00400469 c74424086d6d. mov dword [local_8h], 0x6e616d6d ; [0x6e616d6d:4]=-1

| 0x00400471 c744240c642e. mov dword [local_ch], 0xa0d2e64 ; [0xa0d2e64:4]=-1

| 0x00400479 e8a2ffffff call sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

We can even go further and write these as a series of 8 byte mov’s with the following code.

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

unsigned char* stack_string[20];

((uint64_t*)stack_string)[0] = 0x6f4320726f727245;

((uint64_t*)stack_string)[1] = 0xa0d2e646e616d6d;

printf("%s\n", stack_string);

return 0;

}

This results in the following strings:

010 0x000004f1 0x004004f1 4 5 (.text) ascii =A\v

011 0x00000546 0x00400546 9 10 (.text) ascii Error CoH

012 0x00000554 0x00400554 9 10 (.text) ascii mmand.\r\nH

013 0x0000055e 0x0040055e 4 5 (.text) ascii D$\bH

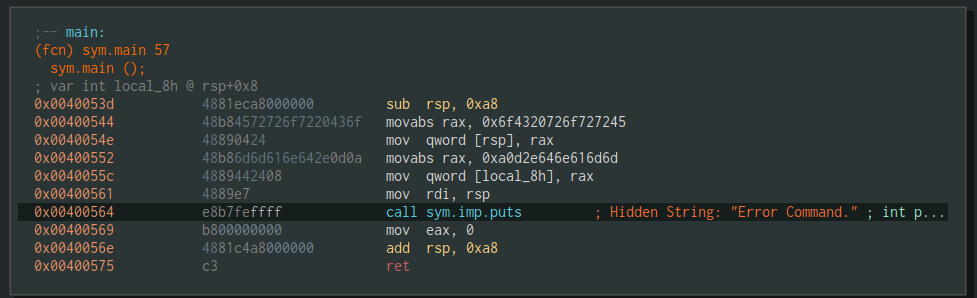

With bigger mov’s more of the string is able to be observed in the strings output. Depending on how the string is pushed, the order may be reversed, which can lead to an oversight when viewing strings output. When viewing the disassembled output, the QWORDS are stored and moved into a buffer.

| 0x00400544 48b84572726f. movabs rax, 0x6f4320726f727245

| 0x0040054e 48890424 mov qword [rsp], rax

| 0x00400552 48b86d6d616e. movabs rax, 0xa0d2e646e616d6d

| 0x0040055c 4889442408 mov qword [local_8h], rax

Note: Modifying compiler optimization can potentially lead to changes in how the strings are constructed in the assembly.

Enter Cutter

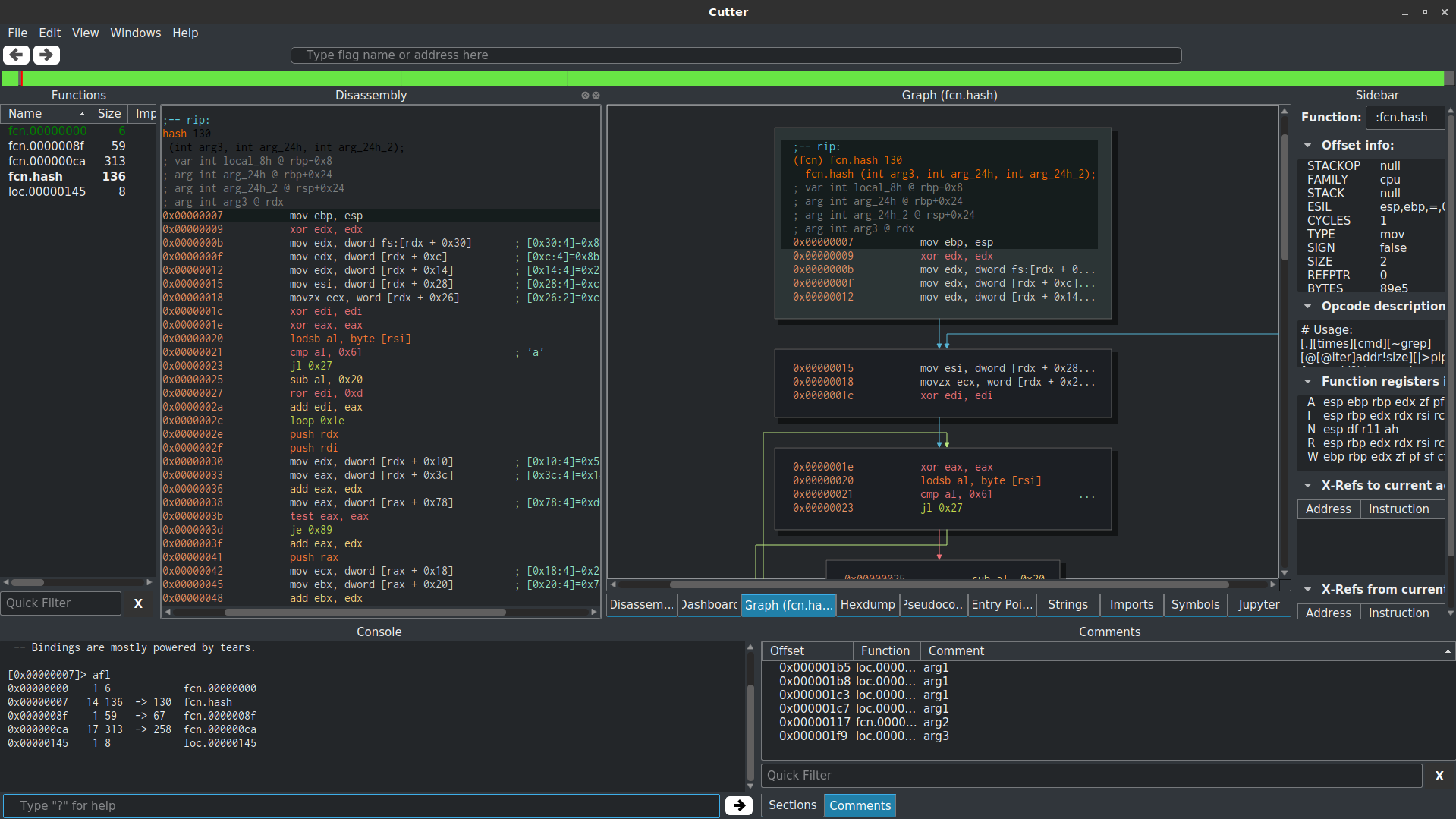

Cutter is the growing and maturing GUI for the radare2 reverse engineering framework. Cutter provides an integrated iPython shell and a scripting interface.

By leveraging both Cutter and Radare, a script can be created that will automatically rebuild and comment the strings, which can be tedious in large binaries.

The script simply crawls each function within the binary and builds a list of candidate stack strings, doing some simple filtering at the end. Once a string is found it’s commented at the appropriate offset.

To open iPython within Cutter, select Juypter from the menu and open the python script.

Opening the 8byte mov binary with Cutter and running the script will produce the following output:

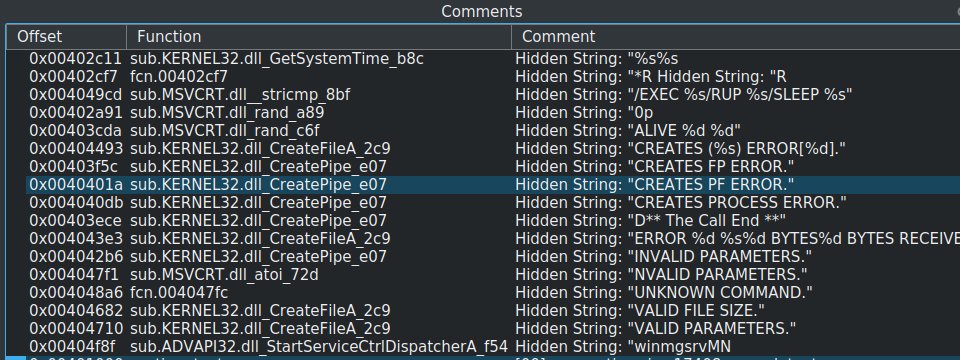

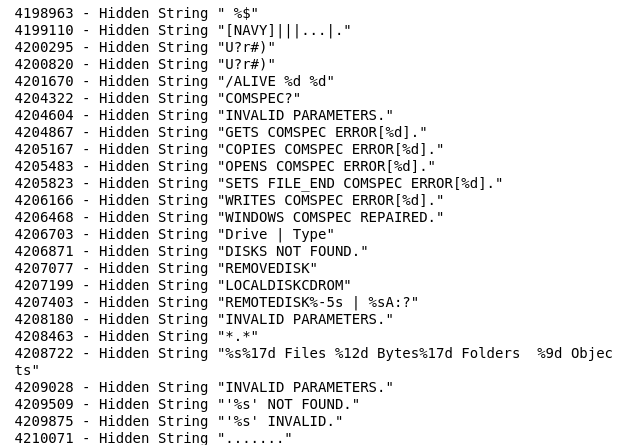

Looking at an APT backdoor like IXESHE, analyzing the backdoor becomes much easier when a script is rebuilding the strings. By viewing the comments section within Cutter, one is able to cross-reference the hidden strings from where they existed within the binary.

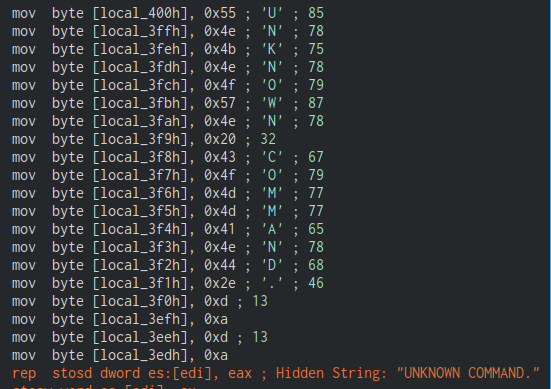

Double clicking on the comment will automatically browse to the location of the comment within the code. By cross-referencing the string at “UNKNOWN COMMAND” we can discern how it was built character by character.

In addition to adding a comment, the script will log the output to the Juypter console.

Conclusion

A full copy of this script can be found HERE on my github. I welcome any improvements.

This method is well documented and not new or unique. With that said, it’s still in use today and many malware zoos do not automatically look for stacked strings, which can, in some cases mislead an analyst. Understanding this method is important to a malware researcher and automating it can save valuable time.

There are plenty of ways to bypass this type of script and we’ll slowly release more tools that deal with these one-off cases. Until then, looking at tools like FLOSS and reading Megabeets excellent writeup of DROPSHOT can provide insight into other methods of decoding and finding strings in malware.

By extending the capabilities of open source software the gap is slowly closing on expensive reversing tools.

Appendix

Some Notes on Rust

While C is easy enough to profile and study, languages like Rust make it a little more difficult. As with C, there exists a variety of ways to hide strings within a Rust application. The hope is that compiled output from rustc resembles source code close enough for the approach detailed in this post to work. Since it doesn’t rely on an intermediate language there’s a good chance the logic above will still work.

Zignatures

When building an application with Rust, one of the first things that is noticed in a disassembler is the sheer amount of functions that even a simple program contains.

This has been blogged about in the past, but if the application is stripped, generating zignatures for a simple rust application can save loads of time analyzing a payload. Zignatures will profile each function and apply the symbol name to any matched functions.

To generate a zignature, use the following commands.

aaa; zg; zos rust_signature_names.zig

To load in zignatures

zo rust_signature_names.zig

Regular Strings in Rust

Consider the following application:

fn main() {

let foo = String::from("On the moon!");

println!("{}", foo);

}

When running strings against the complied application, the ascii strings exist in clear text. It is interesting to note the string appears in section .rodata.

4806 0x00057f00 0x00057f00 13 14 (.rodata) ascii On the moon!\n

If we change the string to mutable and append information onto it the string will still be written to .rodata.

5110 0x00059e70 0x00059e70 126 127 (.rodata) ascii attempt to divide by zerodestination and source slices

have different lengthslibcore/slice/mod.rsOn the moon! And back again!\n

Hidden Strings

A sample program is written using the string push technique provided in Rust’s standard library:

fn main() {

let mut hidden_string = String::from("O");

hidden_string.push('n');

hidden_string.push(' ');

hidden_string.push('t');

hidden_string.push('h');

hidden_string.push('e');

hidden_string.push(' ');

hidden_string.push('M');

hidden_string.push('o');

hidden_string.push('o');

hidden_string.push('n');

hidden_string.push('!');

println!("{}", hidden_string);

}

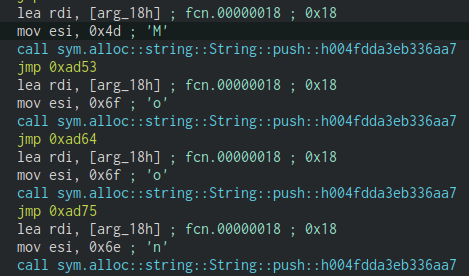

After compiling and opening in Cutter, the following code can be observed.

The script that is written won’t cover this case, but the code is repeatable enough that a modification can be done to rebuild these strings.

Vector to String

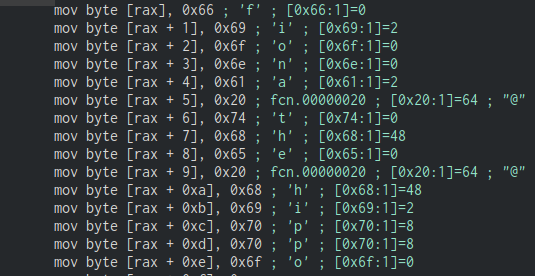

Consider the following code:

fn main() {

let bytes = vec![0x66, 0x69, 0x6f, 0x6e, 0x61, 0x20, 0x74, 0x68, 0x65, 0x20, 0x68, 0x69, 0x70, 0x70, 0x6f,0];

let s = String::from_utf8(bytes).expect("Found invalid UTF-8");

println!("{}", s);

}

If we use the structure to store our bytes of a string as a vector, it’ll conveniently lay out our strings in a C-style manner as seen below. The script posted in this writeup won’t need any modifications to be able to read and reassemble the following string:

The script provided in this writeup gives a good initial base to build upon and cover the fringe cases. One of the best methods of learning is to build small applications that hide strings in a variety of ways and attempt to recover them.