As a reverse engineer on the CBTS Advanced Cyber Security team, I spend a large part of my time pulling apart and profiling the latest and greatest malware. The Mozart malware was hidden from the public for some time. I hope to shed some light on it in this post.

Introduction

The Home Depot breach was a very high profile case this year, which brought the security of point of sale machines into the spotlight. After some mumblings and a bunch of misinformation about who/what and how the attack came about, little pieces of information started to make their way to the surface. Several of which were reports a new malware dubbed “Mozart.”

When I heard of the initial reports behind Mozart, I was eager to get my hands on it. There were very few copies floating around, and the copies available were not being shared. So as you can imagine, I was thrilled when I saw this http://totalhash.com/analysis/1b96a74d8a649dfde269ce2f322732d760c97049.

All the reports out there didn’t have much information on this tool and the deepest level of analysis that I could find was a strings dump of the malware. Not interesting. The purpose of this post is to dig deeper into this elusive tool and talk about how it works so that we can collectively learn and understand.

Diving In

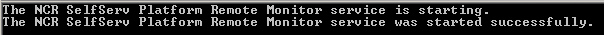

The first thing that this malware does is sets itself up as a service for persistence. It uses a legit looking service name “NCR SelfServ Platform Remote Monitor” with the short name of “NCR_RemoteMonitor”. For those unfamiliar, NCR is a company that specializes in retail point of sale machines. To the untrained eye, these services would look benign. When running the malware for the first time, it’ll pop up a command window with the following text:

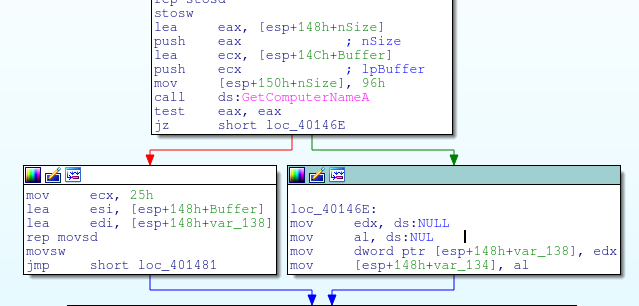

Once the service is set up, it will grab the host name of the system:

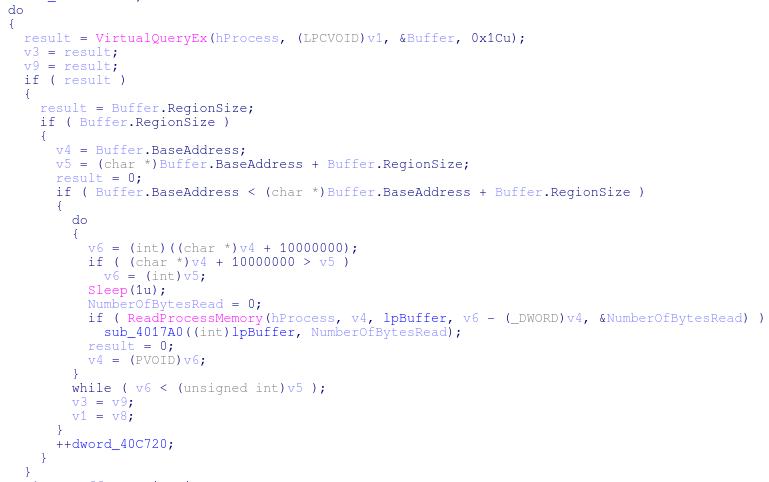

The malware will build the string java.exe (manually from bytes) and then store it. It will later focus on dumping processes named java.exe.

The malware will also grab the current working directory and use that to store “garbage.tmp”. This will be the file where the scraped credit card numbers are staged.

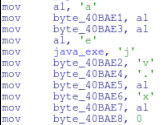

The malware uses a pretty typical combination of GetCurrentProcessId -> EnumProcesses -> OpenProcess -> VirtualQueryEx -> ReadProcessMemory to peer into process memory space to capture unencrypted credit card information that is sitting in RAM.

Chunks of memory are then passed to a function that is responsible for parsing out the track information. The function will look for common sentinels and be responsible for identifying track 1 and track 2 data.

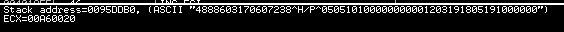

Setting a breakpoint within the function will allow us to see the data being passed around in a buffer.

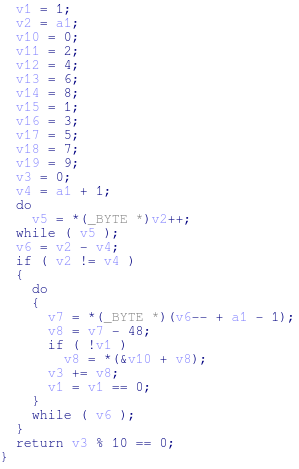

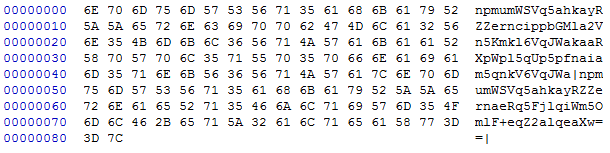

All results are then passed to a function that will use Luhn’s algorithm to validate the code (utilizing a lookup table). This is the defacto algorithm for credit card validation and is a common component in many credit card scraping utilities. A screenshot of Luhn’s pseudocode can be seen below:

Once the data is validated, it is passed to an encoding function that is responsible for doing an ADD and base64 to encode the data and output it to a file. The key that is used for the ADD operation is the string “java.exe”. The encoded information is then stored in garbage.tmp and multiple entries are delimited by ‘|’

A decoder can be written for the data in garbage.tmp using ruby. The following script will decode track information.

#!/usr/bin/ruby

require 'base64'

encoded = "npmumWSVq5ahkayRZZerncippbGMla2Vn5Kmkl6VqJWakaaRXpWpl5qUp5pfnaiam5qnkV6VqJWa|npmumWSVq5ahkayRZZernaeRq5FjlqiWm5OmlF+eqZ2alqeaXw==|"

items = encoded.split('|')

items.each do |elem|

decoded = Base64.decode64(elem)

key = ("java.exe"*10).split(//).map {|x| x.ord}

count = 0

decoded.each_byte do |char|

print "#{(char - key[count]).chr}"

count += 1

end

puts

endWhich when ran, will echo back our track data

ruby ./decode.rb

4888603170607238^H/P^050510100000000001203191805191000000

4888603170607238=05051011203191805191The data that is stored in garbage.tmp will be appended to the file at the hardcoded path “\STWISM\DeviceUpdates\500\athena.dll”. This is particularly interesting as it appears STWISM is the internal name of a server. By having the POS systems dump data to a single location, the attackers needed to retrieve data only from a single spot rather than re-visiting each point of sale machine.

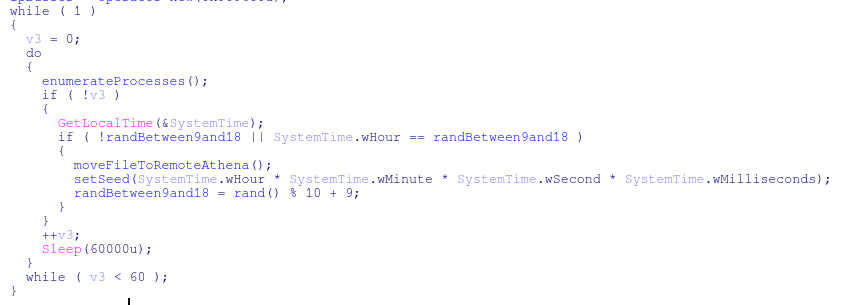

This is done on a random time schedule that is seen (in pseudo code) below, where the malware will check the local time and compare it with the random value. When the backup function is finished, a new value is generated. The numbers that are generated correspond to regular working hours between 09:00 and 18:00.

Oddities

Similar to FrameworkPOS, Mozart contains anti-American messages, including two links to the following sites:

- http://www.the-philosopher.co.uk/whocares/popups/warcrimes.htm

- http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/interventions.html

And a message of “America’s Deadliest Export: Democracy”. These aren’t referenced by code or used in anyway. This is the assumed mechanism the author is using to let the analyst known his/her sentiments.

Another oddity that could give away information about the author is the name of the PDB (debugging symbols) that was used when they were building this file.

- z:\Slender\mozart\mozart\Release\mozart.pdb

There have been plenty of reports speculating information about the Slender persona, so it would be redundant information to dive into that here.

Detection

While this is an older piece of malware, detecting it is still important. At the time of this writing it’s scoring 34/56 on Virustotal. In earlier December it was scoring much more poorly with a total of 5/56. While sharing malware may not be in the interest of the customer, this goes to show that even the AV vendors were not in the loop.

The following yara rule will detect this variant of Mozart:

rule Mozart

{

meta:

author = "Nick Hoffman"

description = "Detects samples of the Mozart POS RAM scraping utility"

strings:

$pdb = "z:\\Slender\\mozart\\mozart\\Release\\mozart.pdb" nocase wide ascii

$output = {67 61 72 62 61 67 65 2E 74 6D 70 00}

$service_name = "NCR SelfServ Platform Remote Monitor" nocase wide ascii

$service_name_short = "NCR_RemoteMonitor"

$encode_data = {B8 08 10 00 00 E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? A1 ?? ?? ?? ?? 53 55 8B AC 24 14 10 00 00 89 84 24 0C 10 00 00 56 8B C5 33 F6 33 DB 8D 50 01 8D A4 24 00 00 00 00 8A 08 40 84 C9 ?? ?? 2B C2 89 44 24 0C ?? ?? 8B 94 24 1C 10 00 00 57 8B FD 2B FA 89 7C 24 10 ?? ?? 8B 7C 24 10 8A 04 17 02 86 E0 BA 40 00 88 02 B8 ?? ?? ?? ?? 46 8D 78 01 8D A4 24 00 00 00 00 8A 08 40 84 C9 ?? ?? 2B C7 3B F0 ?? ?? 33 F6 8B C5 43 42 8D 78 01 8A 08 40 84 C9 ?? ?? 2B C7 3B D8 ?? ?? 5F 8B B4 24 1C 10 00 00 8B C5 C6 04 33 00 8D 50 01 8A 08 40 84 C9 ?? ?? 8B 8C 24 20 10 00 00 2B C2 51 8D 54 24 14 52 50 56 E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? 83 C4 10 8B D6 5E 8D 44 24 0C 8B C8 5D 2B D1 5B 8A 08 88 0C 02 40 84 C9 ?? ?? 8B 8C 24 04 10 00 00 E8 ?? ?? ?? ?? 81 C4 08 10 00 00}

condition:

any of ($pdb, $output, $encode_data) or

all of ($service*)

}

The signature will look for the service names, the filename garbage.tmp, the build path and the encoding routine used to obfuscate credit card numbers.

Conclusion

The malware was compiled on 2014:04:10 18:12:41-04:00. The first rumors of (in the public space) the Home Depot breach was in September. This gives an idea of potentially how long this malware had access to credit card numbers before being discovered.

To me, one of the most surprising things about this malware is how long it was hidden from the malware analyst community. There was a high profile hack, and in the interest of non-disclosure, samples were not shared. It should be an obvious statement that this does not enable the security community and the clients they are protecting, but rather leaves them defenseless as they can’t guard against what they don’t know.

In terms of the malware, this uses fairly common techniques and employs simple protections to prevent itself from being caught. The malware does not utilize a packer and it’ll hide in plainsight by using a service name that looks legitimate. Unlike Dexter, the malware doesn’t use process injection that could potentially set off anti-virus engines. A combination of using Windows networking and only transferring files during work hours, this malware was able to remain undetected for quite some time, proving simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.